If you have the time and inclination, you might want to get acquainted with your major characters at least a little bit before you move on to the next card because characters are quite possibly the single most important element of your novel.

Now, I know from my experiences in my book club that most readers don’t care much about novels this English major appreciates like a really well executed coming-of-age historical mystery set in New York City in 1919. But readers can’t identify with the characters, that is, put themselves in the characters’ shoes, they might not like the book. One of my favorite mystery authors has written a popular series with a hit man as the protagonist. But I just can’t bring myself to read them.

On the other hand, if readers love the characters, they might still love a novel that has a flaw or two. Several of the top novels or series among those on the list of The Great American Read, for example, have rather episodic plot lines. These include Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander that came in as America’s second favorite novel (after To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee), undoubtedly due to the charms of the resourceful time-traveling Claire and her stalwart man in kilts.

During the finale of The Great American Read, Gabaldon confided that when she first was working on Outlander, her husband discovered she had eighty files on her computer named Jamie. You might not want to do that much pre-writing about characters in your novel right now when you haven’t even finished your cards, but it will really help you if you explore them a bit up front.

Here are some methods you might use to get a handle on the characters you made several Novel Basics cards about.

Lots of people, including myself, use a set of basic questions they answer about each major character. My template includes the following: the character’s name, his or her role in the book, gender, age, family and/or cultural background, basic physical appearance, usual manner of dress, distinctive physical feature and/or verbal habit. Also you might want to know the character’s major psychological trait expressed in a single word, ambitious for instance. For mysteries, I also like to know each major character’s secret.

Following the advice of science fiction/fantasy author Orson Scott Card in his book Characters and Viewpoint, part of Writer’s Digest Books The Elements of Fiction Writing series, I keep a character bible for my cozy historical mysteries. If you want to start one now, go ahead.

Sometimes you might let a character audition for the role you intend for her to have. That is, put your protagonist inside one of your obstacle scenes and see what she does and says.

Some writers will interview their characters up front. This is especially useful for the narrator of the story and also for the antagonist. (You might be surprised by what that villain has to say.)

One of my students kept a file on his computer of interesting people he saw that he might want in some future book.

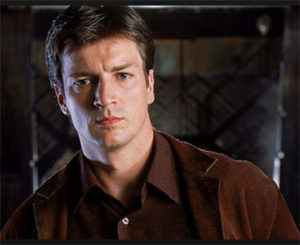

Pin a picture of the character up on your cork board if you have one. I modeled the Prince Charming of my Cinderella, P. I. fairy tale mysteries for grown-ups after Nathan Fillion as Captain Mal in the Firefly series. (Hey, it worked for me.)

So relax for a while, let your imp loose, and get acquainted with some of the characters you might put in your book.

Please come back tomorrow for Card # 8.